The spiritual and moral health of the townsfolk of Mintaro was top of mind from the earliest days, as well as the educational advancement of the minds of the younger generations. The new colonists and settlers brought with them their beliefs and practices from their ‘homelands.’

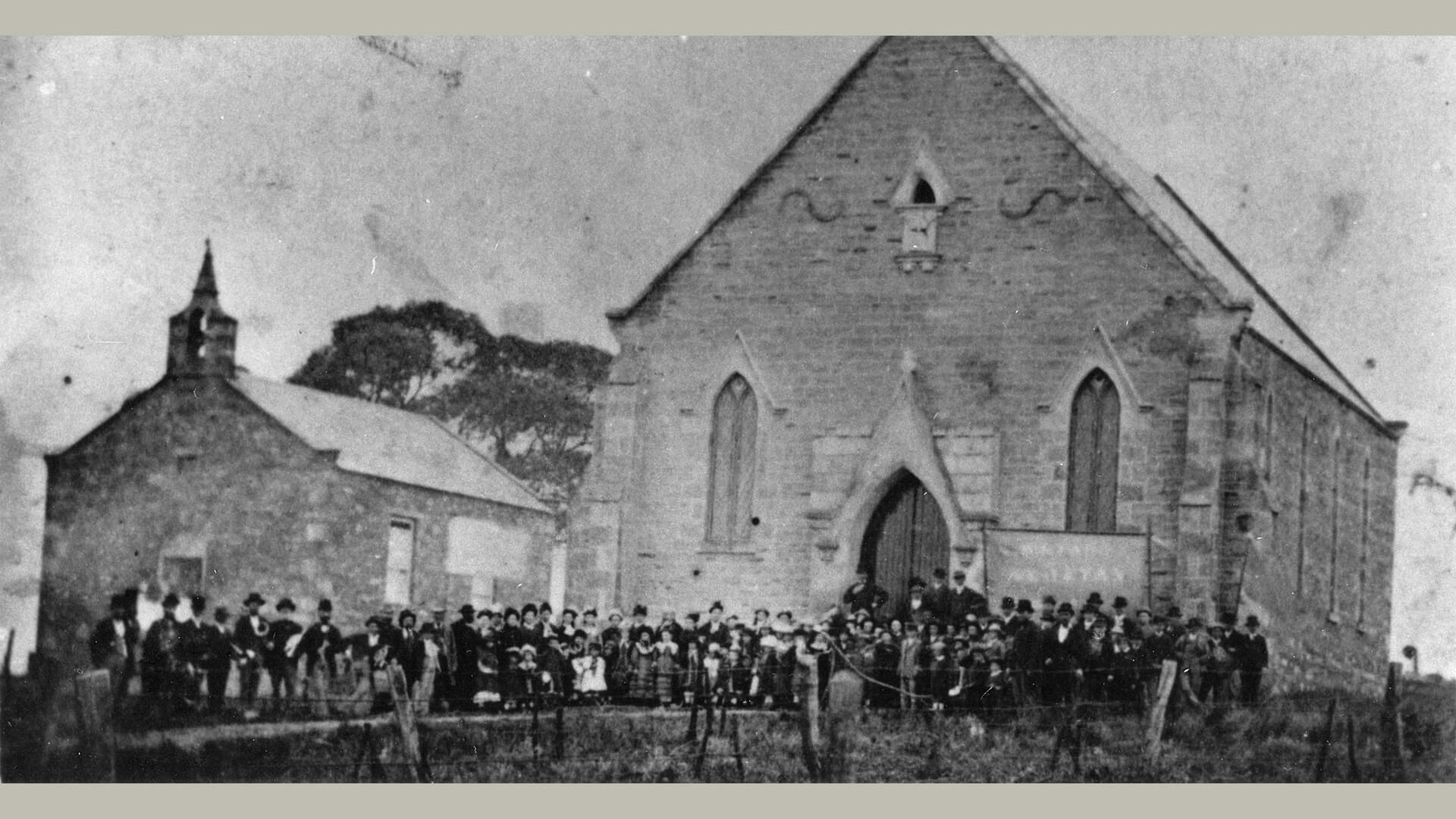

Primitive and Wesleyan Methodists both established chapels as early as 1854, as well as the first ‘school’ in the town.[1][2] A manse, known as the mission house, was built in 1859 to house the resident Wesleyan minister to tend to the growing congregation.[3] As parishioner numbers grew so did the need for larger chapels, the Primitive Methodists building a new one in 1860[4] and the Wesleyans siting their larger gothic-style chapel on high ground, facing the town to the east, in 1867.[5] The Primitive Methodist chapel later became the home of the Anglican faith from 1905.[6]

Irish Catholic Peter Brady settled on land on the northern boundary of Mintaro. He hosted church services in his home for the local Catholic brethren until the Church of Mary Immaculate was built in 1856[7], on land he had conveyed to the church a year earlier. The oldest standing Jesuit church in Australia, it is accompanied by a cemetery for the Catholic faithful and at one time a convent could also be found on the property.

The Protestant community successfully lobbied the government to set aside land for a public cemetery, which opened prior to 1856. The first record in the Mintaro cemetery’s burial register is for 23 year old Sarah Riley from Farrell Flat who was buried in the Catholic section in 1864.[8]

As well as feeding and caring for the soul it was considered as equally important to care for the mind. The first formalised schooling, principally initiated by the Protestant congregation, involved students learning passages from the Bible by heart. These were soon replaced by licensed schools when the Board of Education came into existence but were still managed by the local religious bodies. The Protestants were strong believers in secular education, forming a School Committee and in 1871 buying land for and lobbying the Board for funds to help build a public school. It opened in April 1872[9] and was followed later the same year by the opening of the Convent school at the Catholic church, which had been advocated for by the local Catholic community.[10]

James Fry, appointed in 1870 by the School Committee to be headteacher of the licensed school, became headmaster of the public school when it opened. He remained in that role until 1902 when he retired. The school carried on for another 104 years, eventually closing permanently in 2006, after having amalgamated with the Farrell Flat Primary School 15 years earlier.[11]

Mintaro has a proud history of academic and religious leaders with such names as Jolly, Brown, Quinn, Mortimer, Kelly, Fry and Lathlean.[12][13]