30. Merildin Railway Station & Yards

The Mintaro Station is between six and seven miles from Manoora, and here there is a combined shed as at Riverton, with the addition of a master’s house. At most of the other stopping places the Stationmasters have not residences erected on the spot, owing to the contiguity of neighboring townships, which give the necessary accommodation to the officials in question. This station, however, is four miles east of the Township of Mintaro, and hence the necessity of quarters being built for the Stationmaster.[1] This little known Railway Station complex is historically important for the manner in which it reflects features of the development of the railways in South Australia. The design and detailing of the buildings also mean that it is of architectural interest. The station was built in 1870 when the northern railway line was extended from Roseworthy to Burra.[2] Merildin railway station (once known as Mintaro) sits in solitary splendour in a paddock with the living legacy of the station master’s garden. It too is State heritage listed, but is so remote from the rest of Mintaro that it’s unlikely to find a new purpose in life.[3] “…the last passenger train to use the remaining line to Burra was a SteamRanger tour hauled by former SAR steam locomotive 621 on 19 September 1992. … In theory the line remains open in a dormant condition but has not seen a train in many years.”[4]

Jobs & Housing

As the township of Mintaro grew, and more and more people settled in the surrounding farmlands, the demand for services increased and so did the need for additional skilled workers. People needed somewhere to live, near where they worked. This meant renting or buying land and establishing a dwelling whether it be a tent, slab hut or a stone house.[1] As more permanent structures were required builders, stonemasons, carpenters and labourers were able to find work in and around Mintaro. The slate and other quarries sprang up to supply the stone for these homes, giving work to quarrymen and stonecutters, while local timbers were milled in the town to provide for carpentry and coach-building needs. Carriers, with less work on the Gulf Road, adapted to hauling those goods which couldn’t be sourced locally from larger nearby centres and from Adelaide. As the larger pastoral runs declined, or interest moved further north, land use changed with closer agricultural settlement there was a greater need to have the land fenced, for crops to be planted and harvested, and stock to be fed and watered. This provided opportunities for rural farm labourers to work alongside large land owners and for the many family-based farmers. The pound was established c1851[2] to manage wayward stock (mostly cattle), stockyards were set up for the auction and sale of farm stock and horses[3], local dairies provided milk and the flour mill was built to grind the wheat to supply the daily bread. With this increase in activity openings arose for people to work as land and stock agents, as auctioneers, and in the legal, banking and administrative professions. A tally of the 1870 Adelaide Almanack entries for Mintaro include an auctioneer, engineer, police trooper, Justice of the Peace, schoolmaster, mail contractor and surgeon. Businesses included a flour mill, butcher, fruiterer, 3 storekeepers, 2 saddlers, 4 shoemakers, 2 hotels and 3 blacksmiths, as well as a brickmaker, 3 masons, 5 carpenters, 3 carters and 6 people employed at the slate quarry. On the land one pastoral overseer and 46 farmers were listed.[4] Not bad for a township barely twenty years old! The wine industry and the Clare Valley have been synonymous since the Jesuits settled at nearby Sevenhill in 1849.[5] Wine making and viticulture have become another source of income for the Mintaro region. Tourism followed in the 1900s, particularly since Mintaro’s significant heritage was recognised in 1984[6], with many finding work in accommodation, catering and other areas of hospitality.

Faith & Education

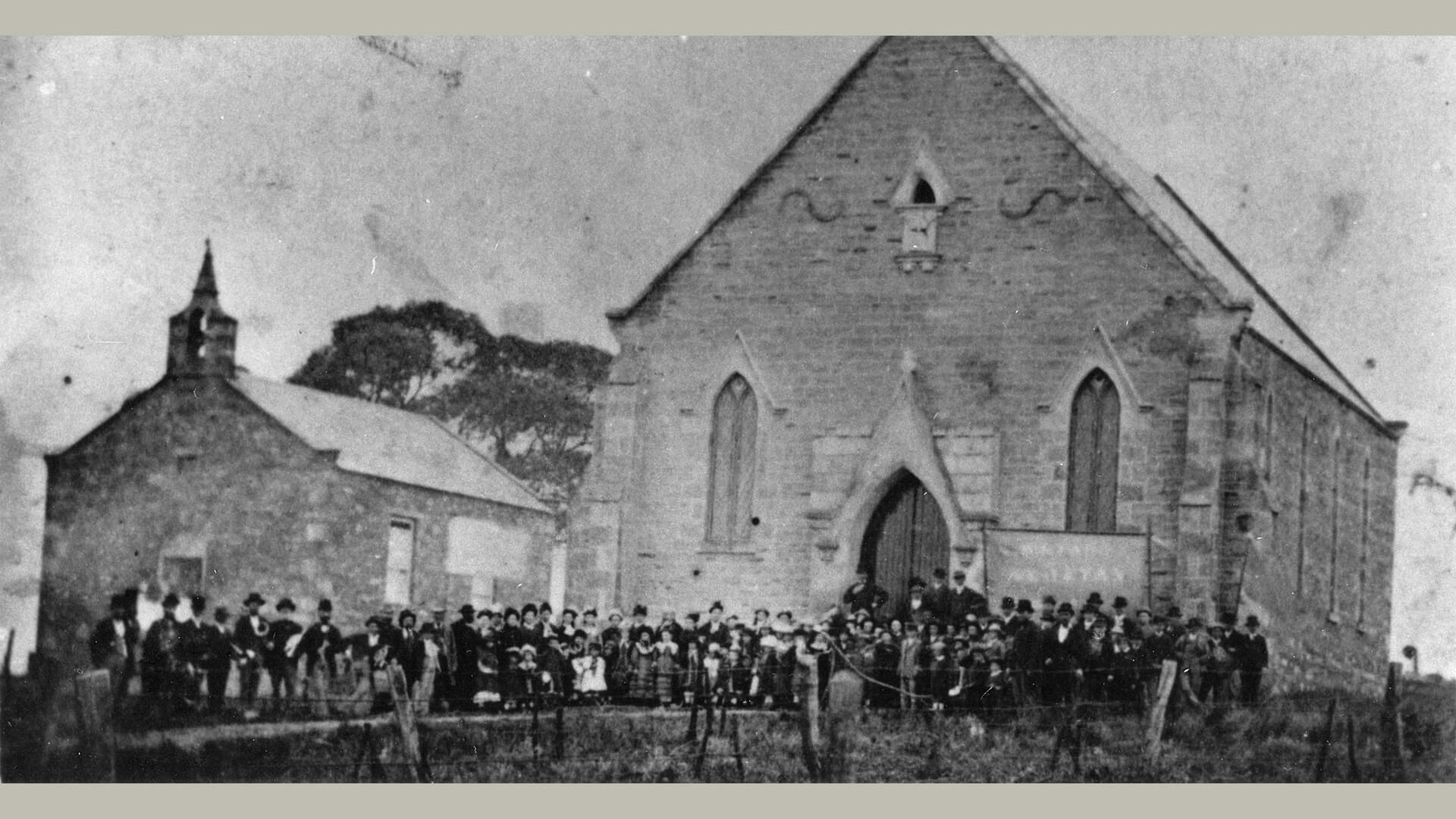

The spiritual and moral health of the townsfolk of Mintaro was top of mind from the earliest days, as well as the educational advancement of the minds of the younger generations. The new colonists and settlers brought with them their beliefs and practices from their ‘homelands.’ Primitive and Wesleyan Methodists both established chapels as early as 1854, as well as the first ‘school’ in the town.[1][2] A manse, known as the mission house, was built in 1859 to house the resident Wesleyan minister to tend to the growing congregation.[3] As parishioner numbers grew so did the need for larger chapels, the Primitive Methodists building a new one in 1860[4] and the Wesleyans siting their larger gothic-style chapel on high ground, facing the town to the east, in 1867.[5] The Primitive Methodist chapel later became the home of the Anglican faith from 1905.[6] Irish Catholic Peter Brady settled on land on the northern boundary of Mintaro. He hosted church services in his home for the local Catholic brethren until the Church of Mary Immaculate was built in 1856[7], on land he had conveyed to the church a year earlier. The oldest standing Jesuit church in Australia, it is accompanied by a cemetery for the Catholic faithful and at one time a convent could also be found on the property. The Protestant community successfully lobbied the government to set aside land for a public cemetery, which opened prior to 1856. The first record in the Mintaro cemetery’s burial register is for 23 year old Sarah Riley from Farrell Flat who was buried in the Catholic section in 1864.[8] As well as feeding and caring for the soul it was considered as equally important to care for the mind. The first formalised schooling, principally initiated by the Protestant congregation, involved students learning passages from the Bible by heart. These were soon replaced by licensed schools when the Board of Education came into existence but were still managed by the local religious bodies. The Protestants were strong believers in secular education, forming a School Committee and in 1871 buying land for and lobbying the Board for funds to help build a public school. It opened in April 1872[9] and was followed later the same year by the opening of the Convent school at the Catholic church, which had been advocated for by the local Catholic community.[10] James Fry, appointed in 1870 by the School Committee to be headteacher of the licensed school, became headmaster of the public school when it opened. He remained in that role until 1902 when he retired. The school carried on for another 104 years, eventually closing permanently in 2006, after having amalgamated with the Farrell Flat Primary School 15 years earlier.[11] Mintaro has a proud history of academic and religious leaders with such names as Jolly, Brown, Quinn, Mortimer, Kelly, Fry and Lathlean.[12][13]

Sport & Leisure

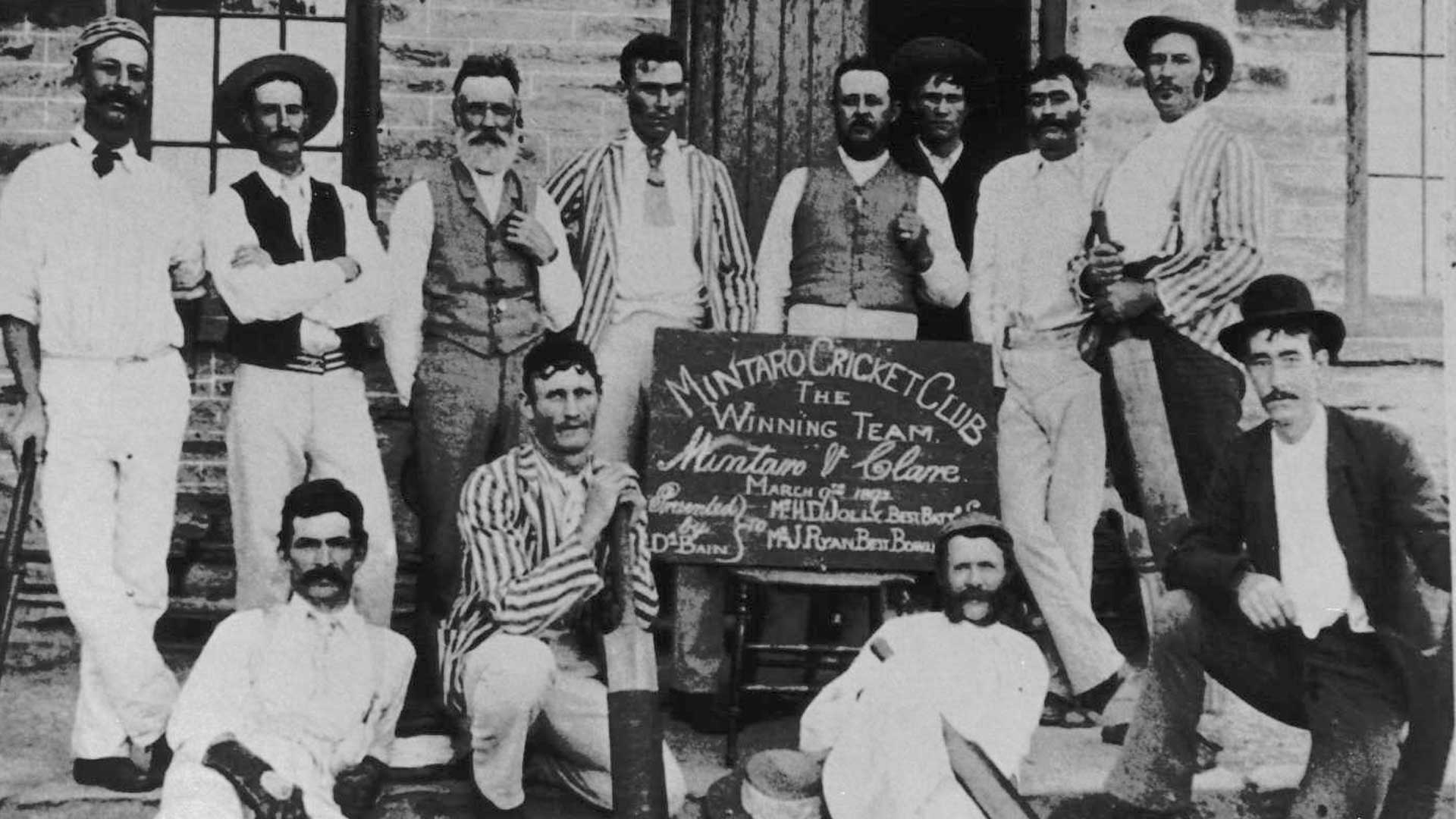

Mintaroites have always loved their sports and leisure activities. Outside of work, family and spiritual duties these activities provided opportunities for building social cohesion. Some of the earliest recorded activities, such as fox hunting and horse racing, reflect the homeland origins of the settlers.[1][2][3] Coursing, or live hare racing, started at Mintaro in 1884 and was well patronised up until it was outlawed in 1986.[4] Interestingly, Joseph Gilbert, one of the founder brothers of Mintaro, was the first person to import hares into South Australia.[5] These were soon followed by cricket—the first matches being played in the town on the land which is now Torr Park[6]—along with football and tennis. Torr Park also had a Croquet court, laid down in 1929[7], and now hosts the Mintaro Bowling Club, established in 1959[8], alongside the tennis courts and the children’s playground. Mintaro had a football team as early as 1881, the newspaper reporting ‘Football matches are the order of the day, and to distinguish one side from the other the most fantastic dresses are worn.’[9] In 1911, in response to a public request, W. T. Mortlock donated 11 acres of land on the southern edge of the town for a recreation reserve, to be known as Mortlock Park.[10] Mintaro Football Club was admitted to the Mid-North Football Association in 1932.[11] Mintaro Netball Club entered the North Eastern Association in 1976, at the same time as Min-Man Football Club.[12] For those whose leisure pursuits were less athletic in nature there were the regional agricultural and horticultural shows in the later 1800s where residents and local farmers could show off their gardening and produce-making skills.[13] There were also ploughing competitions where they could demonstrate their talents with the latest in farming equipment.[14] And then there were the picnic days and sports galas of the late 1800s and early 1900s[15][16], as well as the major events such as the State’s Centenary in 1936 which brought all the town and rural folk out to celebrate.[17] Originally public meetings, celebratory events, dances and other such events were held in the hotels, especially the Devonshire Inn which had a very large room and, for a time, a downstairs bowling alley. When it opened in 1878[18], the Mintaro Institute became the hub for these social events and the venue for travelling shows and entertainments that came to the town.[19] The Institute continues to be a centre for meetings, functions, events and festivals. It is complemented by Mortlock Park and Torr Park, which continue to be developed to provide the best possible sporting and recreational facilities for the people of Mintaro and surrounds.

Rates, Roads & Rail

The collection of rates and taxes for public services and the administration and management of these services was undertaken by the local council of the time. Clare council had responsibility for Mintaro until 1868, then the District Council of Stanley from 1868-1932, Clare again from 1932-1997, and currently the Clare & Gilbert Valleys Council.[1] Services included keeping records of land transactions for issuing rates, maintaining roads, bridges and other infrastructure, often at ratepayer’s requests, the licensing of business and trades such as hotels and butchers, appointing ‘constables’, and the oversight of weed and vermin control. The council often worked in collaboration with the local elected members in the State parliament to raise issues of relevance to their community members particularly in regard to requesting financial assistance for major projects beyond their limited resources. G. S. Kingston and H. E. Bright are both recognised in street names in Mintaro.[2] Another key supporter of Mintaro was A. J. Melrose MP, then owner of the Kadlunga estate. When the District Council of Stanley was established in 1868 W.E. Giles was appointed the first clerk. He worked out of a shop in the complex opposite the Post Office until the newly completed District Hall was opened in 1877. He retired in 1908 after 40 years serving his community.[3] Messrs. John Pearce, Joseph Williams, Henry Jolly, Thompson Priest, and Alexander Melville, were nominated to be the first Councillors of the district.[4] Melville became the first Chairman of the new council.[5] A year later in 1878, after funds had been raised through public subscription and with matching support from the government the Mintaro Institute was opened.[6] It had a library and a reading room where subscribers could read the newspapers of the day to stay informed. After Stanley Council was reabsorbed into Clare Council the chambers operated as a banking agency for a time. Then, in 1942, the Institute and former chambers were joined with a shared annexe between them to form the present Institute.[7] Mintaro was a rowdy place at times, and had its share of petty crimes and scams. In the early years of the township citizens were appointed as ‘constables’ to ensure social sobriety and to report on disturbances to the nearest police station. They could also be called on to be present at inquests into deaths and other events. As the town grew larger it was recognised that a permanent policing presence was needed and a police station and lock-up were commissioned. The police station was opened in 1868 and was closed permanently about 1946.[8][9] The arrival of the railway in 1870[10] also brought great change, providing access for residents to larger centres in the region and to Adelaide itself. Farmers and businesses benefitted as well with the trains enabling the freight of goods and produce to larger markets in the State and interstate. The railway station was built four miles (7km) east of the town and necessitated improvements to the roads between them, including a bridge over Wockie Creek. Communications improved when the telegraph was connected from the station to the town in 1878.[11] A temporary township grew up around the railway station, even boasting a licensed school for a number of years; this has all since disappeared. A private subdivision for the Township of Ennis, north of the station, was created in 1871 but this also did not survive.[12]

Settlement

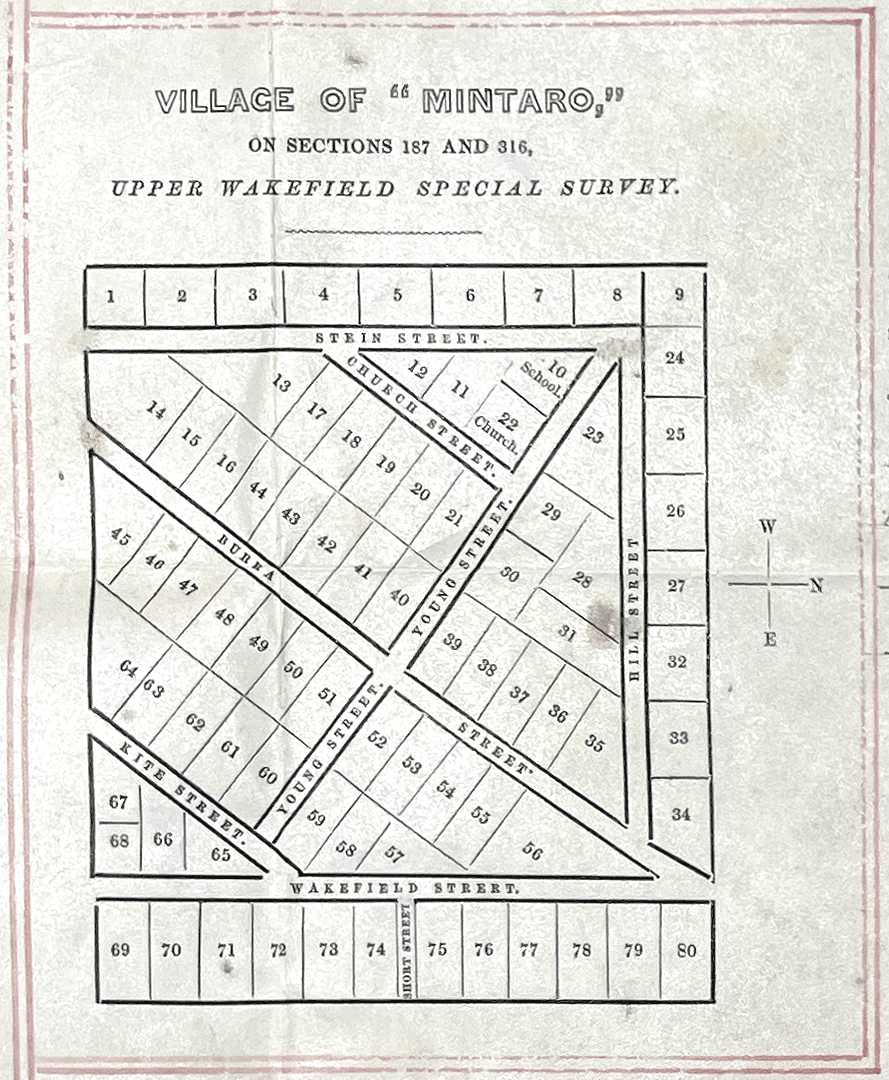

Located on the traditional lands of the Ngadjuri people, the Township of Mintaro was established in 1849 by brothers Henry and Joseph Gilbert. The mid-north area in the new colony of South Australia, of 1836, was first explored for suitable tracts of grazing and agricultural lands in 1839 by Europeans John Hill, who named the Wakefield and Hutt Rivers, and Edward John Eyre a month later, who named the Hill River.[1] Following Hill’s exploration the Upper Wakefield & Hill Rivers Special Survey was taken out in 1840 by his friend John Morphett ‘on behalf of the absentee owner, the philanthropist Arthur Young (1810-95) of Aberdeen, Scotland.’[2] First squatters to be granted occupation licences, in 1841, were Charles J. F. Campbell at Hill River and James Stein who founded Kadlunga.[3] ‘In 1844 overlander William Robinson (1814-89) established Hill River station, later known as the Hill River Estate, or the Hill River run, which became one of the great South Australian pastoral properties of the 19th century.’[4] Copper mining began at Burra in September 1845 after ‘William Strear (or Streair), a shepherd employed by Stein, found the ore sample that led to discovery of the fabulously profitable Burra copper mines.’[5] To reduce the cost and time to cart ore to Port Adelaide for shipping to smelting works in South Wales the Patent Copper Company (later the English and Australian Copper Company) established a private road in 1849, a carting route, to Port Wakefield (briefly Port Henry), which became known as the ‘Gulf Road’ (1849-1857). The company bought sections in the Upper Wakefield Special Survey—including Kadlunga, a watering hole on the Gulf Road at the time—and established a farm to service the agricultural needs of both stock and the people of Burra. When the road was re-routed to the east of Kadlunga, solicitor Henry Gilbert applied for and, on 1st December 1849, was granted Sections 187 & 316 for £160.[6] He later sold them to his older brother Joseph, of Pewsey Vale, in November 1850 for 10 shillings.[7] The Township of Mintaro was subdivided into allotments and sold, the first recorded sale being allotment 55 to William Tatum of Crystal Brook in November 1849.[8] Another subdivision, Mintaro North, was added in 1867 by Peter Brady. 1851-52 saw mass departures from South Australia for the Victorian gold fields, including the dray drivers and their bullock teams. This prompted the English and Australian Copper Company to import mules and muleteers from South America, first in 1853 on the Malacca from Montevideo, Uruguay, and later from Valparaiso, Chile.[9] Good slate deposits were found in the early 1850s west of the town on land owned by Peter Brady. In 1856 the Mintaro Flagstone Quarry was opened, under lease by Thompson Priest, an English settler and stonemason.[10] During this time Mintaro was a busy place with up to 200 bullock drays recorded as travelling along the Gulf Road.[11] A year later in 1857 when the drays were redirected to the new railhead at Gawler they disappeared from the Gulf Road along with most of the teamsters and muleteers. Initially a setback for Mintaro, it emerged from the loss of the copper traffic to become a major centre for slate mining and agriculture.[12] A few of the teamsters remained and settled in Mintaro and, along with the earliest settlers of the township, the Cornish miners hired by Thompson Priest and the Irish, Scottish, and English immigrants drawn to South Australia by the governments assisted passage scheme, as well as the Polish immigrants fleeing persecution in their homeland, the foundation for Mintaro’s diverse community was set.

Hotels & Shops

Mintaro, one of the watering stops on the Gulf Road between Burra and Port Wakefield, was initially established as a service centre for the passing trade. With the subdivision of the Hundreds of Clare (proclaimed 1850), Upper Wakefield (1850) and Stanley (1851) farming land also became available.[1] Colonists arriving in Adelaide on assisted passage moved north to take up these sections, increasing the demand for services. Mintaro Hotel opened in December 1850 providing accommodation for teamsters and stabling and stockyards for their bullock teams.[2] The Devonshire Inn followed in 1856.[3] Some of the earliest businesses to set up were wheelwrights, saddlers and bootmakers, keeping the drays in repair and the teamsters and muleteers shod. Butchers and general stores opened to fulfil the needs of the passing trade. Greengrocers and bakers were not far behind. The building of the town’s flour mill in 1858 provided wheat farmers an outlet for some of their harvest.[4] The township even boasted a brewery.[5] Land agents and auctioneers were soon part of the mix, managing the increasing number of property, stock and machinery sales. Postal services came to Mintaro as early as 1856 and the telegraph station was opened in 1873.[6][7] After the change of route for the bullock drays in 1857 to the Gawler railhead, and later Kapunda, bypassing Mintaro, businesses changed and adapted. Blacksmiths began producing agricultural equipment and some of the carters bought land to begin farming themselves. By 1863 Mintaro was reported to be ‘…still having further improvements in our township. Our worthy miller is still adding buildings to his property, which helps to enliven us. Our little township now consists of three places of worship (good buildings), two stores, two blacksmiths’ shops, three carpenters’ shops, two public-houses, three butchers’ shops, one school and one steam flour-mill.’[8] A Justice of the Peace and legal services, a registrar for births, deaths and marriages, and a doctor were all part of the growing town. Friendly societies, such as the Foresters, Rechabites and Oddfellows[9][10][11], established chapters in the town to help provide ‘social services’ for the townspeople.

Ngadjuri – Traditional Owners

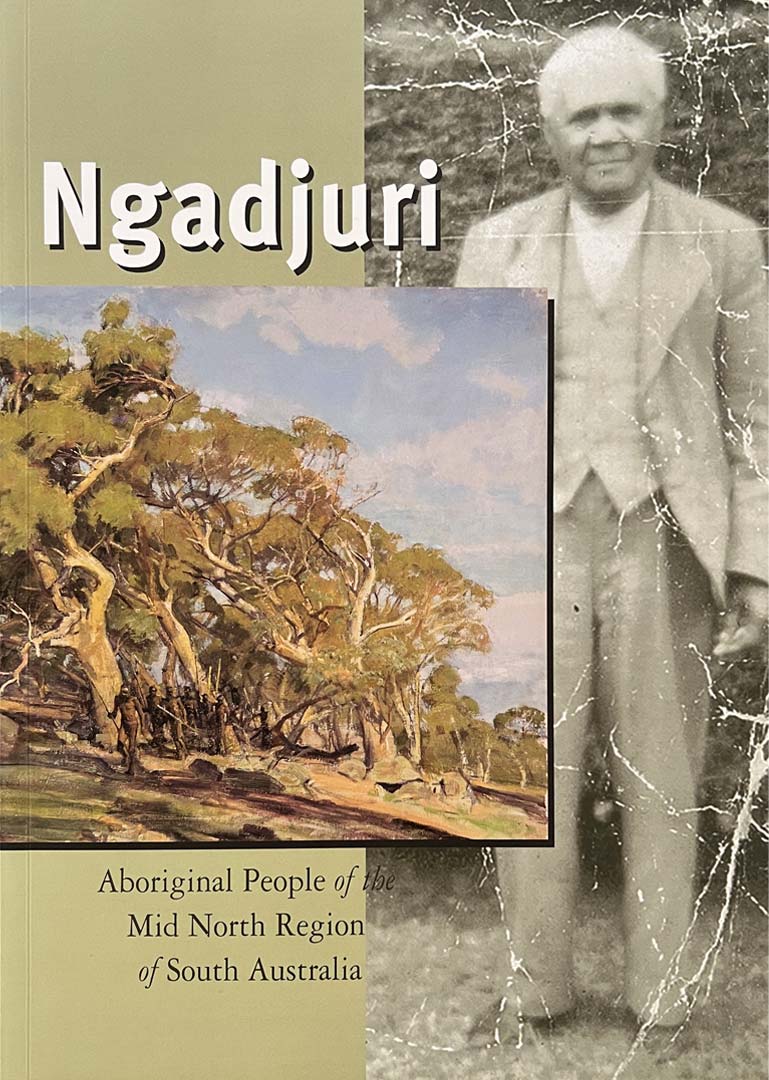

Ngadjuri people are the Traditional Owners of this region and have lived here for many thousands of years. The word ‘Ngadjuri’ in their language means ‘we people’. They are also known as the ‘hills people’ and ‘peppermint gum people’. There are remnants of ‘peppermint box’, Eucalyptus Odorata, throughout Ngadjuri Country. Ngadjuri Country covers much of South Australia’s Mid North. It extends from Gawler in the south, to just east of Quorn in the north-west, and beyond Mannahill in the east. Archaeological, anthropological and ethnographic history offers rich evidence of Ngadjuri culture all through this region. Many rock surfaces are alive with Aboriginal carvings and paintings of great antiquity. Stone tools, message stones, spear points, fire hearths, rock shelters, scar trees, and grave sites all tell their own stories of Ngadjuri people and their ongoing connection to this land. Ngadjuri found it increasingly difficult to hold onto their land. The new settlers took over many water and food sources. They also brought in new diseases, to which Ngadjuri had no immunity. Violence broke out at times. Many Ngadjuri people died, with estimates that only about 10 percent of the population survived those first few decades of contact. Many survivors were forced onto missions across South Australia, including the Poonindie Mission on Eyre Peninsula, Point Pearce Mission on Yorke Peninsula, and Point McLeay Mission in the Coorong area. Other Ngadjuri people joined neighbouring Aboriginal groups living north, east, and west along the Murray River. Many Ngadjuri people are involved in protecting their rich heritage, and revitalising their living cultural landscape for all to enjoy and learn from. The names of many towns and areas in the Mid North offer hints about Ngadjuri knowledge, like these words to describe parts of the landscape. For Example: Booborowie, round waterhole; Bundaleer, among the hills; Caltowie, waterhole of the sleepy lizard; Canowie, rock waterhole; Coomooroo, small food seeds; Eudunda, sheltered water (originally Eudunda Cowie, from the word judandakawi); Kapunda, water jump out; Tarcowie, flood water or place of washaway water; Terowie, hidden waterhole; Yacka, sister to the big river; and Yarcowie, wide water. This information has been sourced from the book Ngadjuri – Aboriginal People of the Mid North Region of South Australia, written in 2005 consultation with the Ngadjuri Walpa Juri Lands and Heritage Association. Other sections have been written more recently in consultation with Ngadjuri people who have been working with the Clare and Gilbert Valley Council on cultural revival projects. Further information; please contact the Ngadjuri Nation Aboriginal Corporation; Ngadjuri Walpa Juri Lands & Heritage Association; or the Clare & Gilbert Valleys Council.

02. Mintaro Post Office

The Mintaro Post Office was built in 1883, although the township has had a postal service from 1866. The simple sandstone and brick building was built to a standard design repeated in many country towns. The sandstone is tuck pointed with black lining and red brick curved plinths are used. The Post Office Building is listed as a State Heritage Place on the State Heritage Register. It passed from The Commonwealth into private ownership in 1930 when it was sold to Frank McNamara for £4100. The McNamara’s continued to operate the postal agency until 1979 when it was sold to Stephen and Marilyn Geier. Since then, the building and postal agency has changed hands on four occasions. Various additions to the building were added over these years but recent conservation work has seen these removed. The postal agency continues to operate as the town’s distribution centre for letters and parcels, now for one hour a day, Monday to Friday. Banking agencies and other services are no longer provided.

04. Central Business Complex

The row of shops across the main street from the Post Office and Devonshire House was built in the 1850’s to service Mintaro’s commercial needs. The traditional ground floor commercial layout was complemented by upper floor living accommodation. In 1853 Joseph Gilbert sold Allotment No. 37 to shoemaker John Huxtable and then sold the northern section to James McWaters, a farmer, in March 1857. Lot 36, to its north, was originally owned by Frederick Leighton, a blacksmith who operated a forge and had stables behind the main building, the sections of the buildings over time were used for a variety of services and retail enterprises including fodder stores, a fruit and vegetable shop, a delicatessen that provided lunches to the Slate Quarry workers, a butcher and a branch of the ES&A Bank. Various families occupied the living areas until the 1980’s when both buildings were purchased by ‘entrepreneurs’ and renovated and converted to a small general store, tearooms, a restaurant and small conference centre and Bed and Breakfast accommodation, incorporating the attic bedrooms. Slate, a feature of many Mintaro buildings, has been used extensively to construct walls and paving on the ground floors and verandas. Stone horse mounting steps, originally located in front of the Post Office, are now a feature at the front of the shops, between an incredibly old Pepper tree and equally ancient Moreton Bay fig tree.